“If you want to understand the secrets of the universe, think in terms of energy, frequency and vibration”

Nikola Tesla

What do these words mean ?

A vibration is a movement up and down :

A frequency is the number of movements up and down per second, called hertz.

Energy is the ability to move, it is what fuels the movement up and down.

Sound is created by this motion up and down, when our vocal strings vibrate or when the wings of an insect go up and down, it creates a sound. A guitar tuned to 432hz means that when one of its string is plucked it will go up and down 432 times per second. Since frequencies spread in their environment, the body of the guitar will start to vibrate along with this frequency, and so will the surroundings of the guitar, including people.

This is a powerful force, see how a voice can shatter glass.

Many studies have proven the effects of music on our physical, mental and emotional health.

There are several aspects in music : the emotional and mental energy in it, the intention behind it, and the physics of it : its frequency, geometry, etc.

Positive intentions, emotions and thoughts in music can provide healing regardless of its physics, but proper physics can take the healing to a whole other level.

The 432hz tuning means that the middle A note will have that frequency. Then all the other notes will tune accordingly on different frequencies along the scale. So 432hz is just a reference point.

If you watch any orchestra or band, they will always tune together to the exact same reference point frequency. If even just one instrument is out of tune with the others, the whole thing will sound off.

Jamie Burtuff explains that European music before the early 50s, ancient Egyptian music, traditionally made Tibetan bowls and digeridoos, sitar Indian music, and many others, have been tuned to 432hz. I have also measured sounds of Wolves, Whales and Dolphins singing and some Amazonian shamans and they were all using these frequencies.

Around the second world war, the cabal studied which tuning would be the most harmful for humans, and as a result imposed the 440hz tuning via Goebbels (who thought it was the best for war marches), and JC Deagan. Musicians at the time protested against it but it was pushed through anyway. Almost all music has been tuned to that since then.

Since the new age movement, there has also been another tuning circulating called solfeggio, based on a middle C note of 528hz. This corresponds to a middle A of 444hz.

Although the numbers used for these frequencies do correspond to geometrical patterns found in nature, it appears they do not correspond to frequencies : as you can see in

this video at the 6min6 mark, these frequencies are not harmonious between themselves, which means that it is not possible to play any music with them. So when you listen to music made with these frequencies, there can only be one note that will be part of this solfeggio frequency scale, and the rest of the music will not be part of it, which raises questions about its validity.

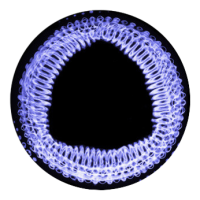

John Stuart Reid has shown the shape created by 432hz with cymatics (the science of making sound visible by vibrating water or other types of particles) :

This is the basis of so much universal geometry, if not all. This is where the flower of life pattern is born, from which all platonic solids can be derived among other things :

This means that, as the cymatics show, 432hz will create this geometry in physical matter, which include our own bodies.

A very professional 28 pages scientific study has been published showing clear reducing of inflammation, stress levels and other symptoms by listening to 432hz music in Pythagorean tuning only three times, for 35min each time, in a period of 7 days. You can read the whole study here :

http://fr.scribd.com/doc/202351974/Spiritual-Results-

(Note : The Pythagorean tuning (also called just intonation), is a separate, independant and complementary aspect than the 432hz aspect. The 432hz is the reference point, and the Pythagorean aspect is the space between the different notes in the scale. Click here to learn about it)

Scott Onstott in Secrets in Plain Sight has shown how our measurement systems such as miles and meters are not random but correspond to natural distances found in nature. Therefore they resonate with sacred geometry.

In music, the same note on higher and lower octaves is found by dividing or multiplying the frequency by two.

Scott Onstott also showed that the number 432 and its octaves are found frequently in measurements of space and time throughout our galaxy, for example in the dimensions of our Sun (432 000 x 2 = 864 000 miles diameter) and Moon (4320 ÷ 2 = 2160 miles diameter), and in the 25920 years of the galactic cyle/procession of the equinox : 432 x 60, 60 being at the basis of how we measure time. This seems to me to be the basis for the music of the sphere. Additionally the speed of light is 432 x 432 miles per second, there is 43200 x 2 seconds in a day, and our solar system is travelling inside the galaxy 43200 miles per hour. (

More info about this here)

Everything in creation, all matter is in a state of vibration. 432hz is in tune with the frequency of nature throughout the cosmos. If humans are out of tune with it, it creates discomfort. Listening to music in 432hz helps us realign with our environment and the natural geometric patterns of the universe, promoting well-being physically, mentally and emotionally.

Now, here is how to convert any music from 440hz to 432hz

(Note : This protocol is to convert music from 440hz to 432hz. If the music was originally made in 432hz then using this protocol will make it out of tune. Almost all music nowadays is in 440hz, except a lot (but not all) of Indian traditional music which is still made in 432hz, as well as some traditional Tibetan or didgeridoo music, and a few other isolated cases.

)

Download the free software Audacity here

Then download this little plug-in here in order to be able to save files in mp3

First we need to create a protocol, and then you will be able to apply it quickly and easily to any file or group of files.

Open Audacity, click on the ‘File’ tab on the top left corner, then ‘Edit chains’, and then ‘Add’ on the bottom left corner.

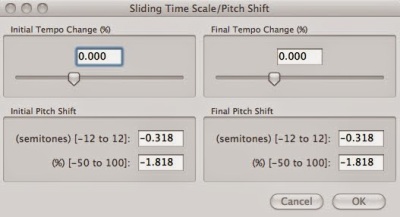

Enter the name you want for the protocol, for example 432, then click on insert. Then double click on ‘TimeScale’, and then edit parameters.

Then type -1.818 in both (%) boxes and click Ok :

Then click ok again, then click on insert, and double click on ‘Exportmp3’, and click Ok.

That’s it ! Click ok to leave this box, and now anytime you want to convert a file, click on ‘File’, ‘Apply chain’, select the 432 protocol, and click on ‘Apply to files’, select the music files you want to convert and it will be done automatically. You can select as many files as you want and the converted files will be placed in a new folder named ‘cleaned’, inside the folder where the original file was.